16 States of Palau: Hatohobei

2025/5/23

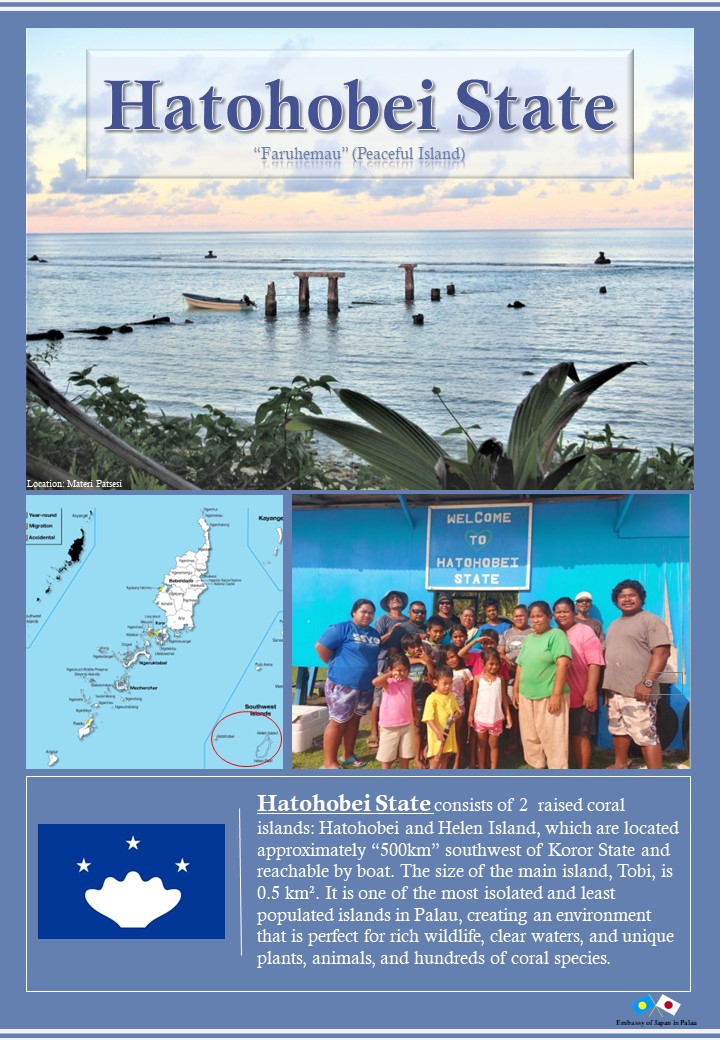

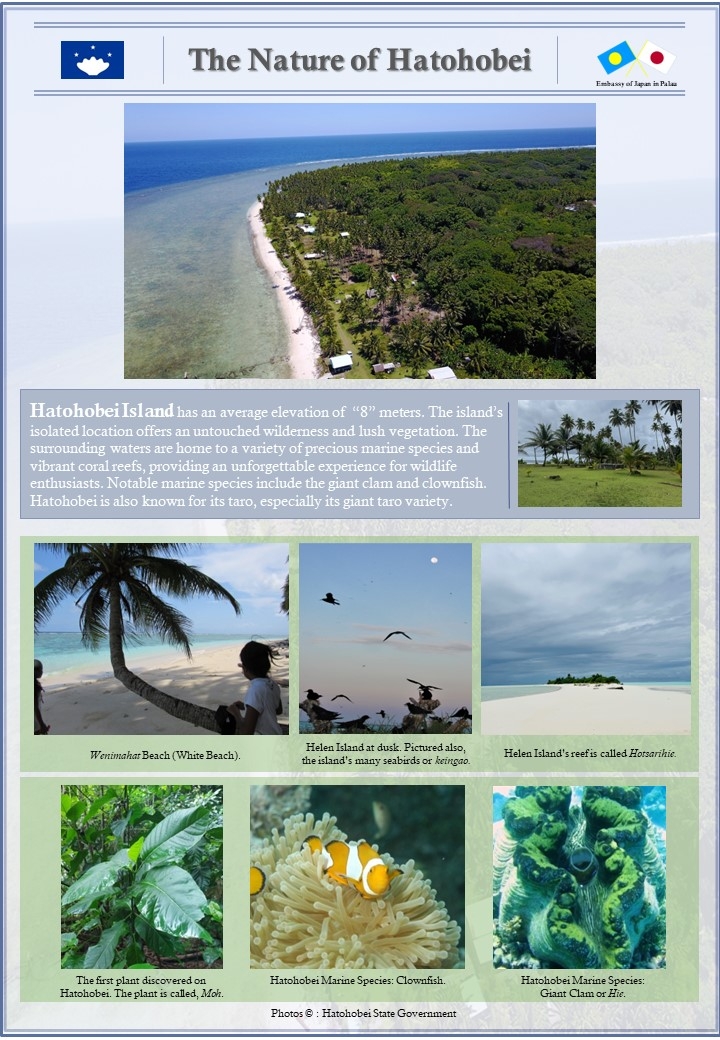

An Introduction to Hatohobei State

More Historical Landmarks of Hatohobei State

Interview with Ms. Huana K. Nestor: Stories from the Past & Moving Forward

On January 29th, 2025, we interviewed Ms. Huana K. Nestor, former Governor of Hatohobei State. Ms. Huana told us stories from the time of World War II, stories that her and other older Tobians are familiar with. She also shared with us the efforts that her and the women’s association of Hatohobei have been working on to keep traditional culture alive.

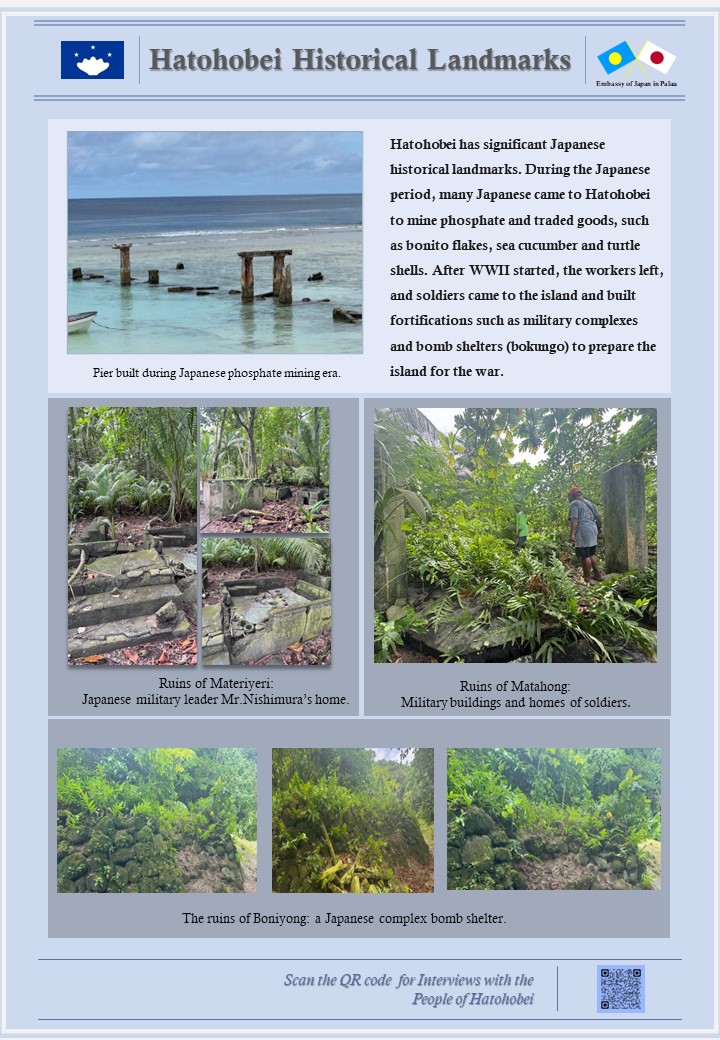

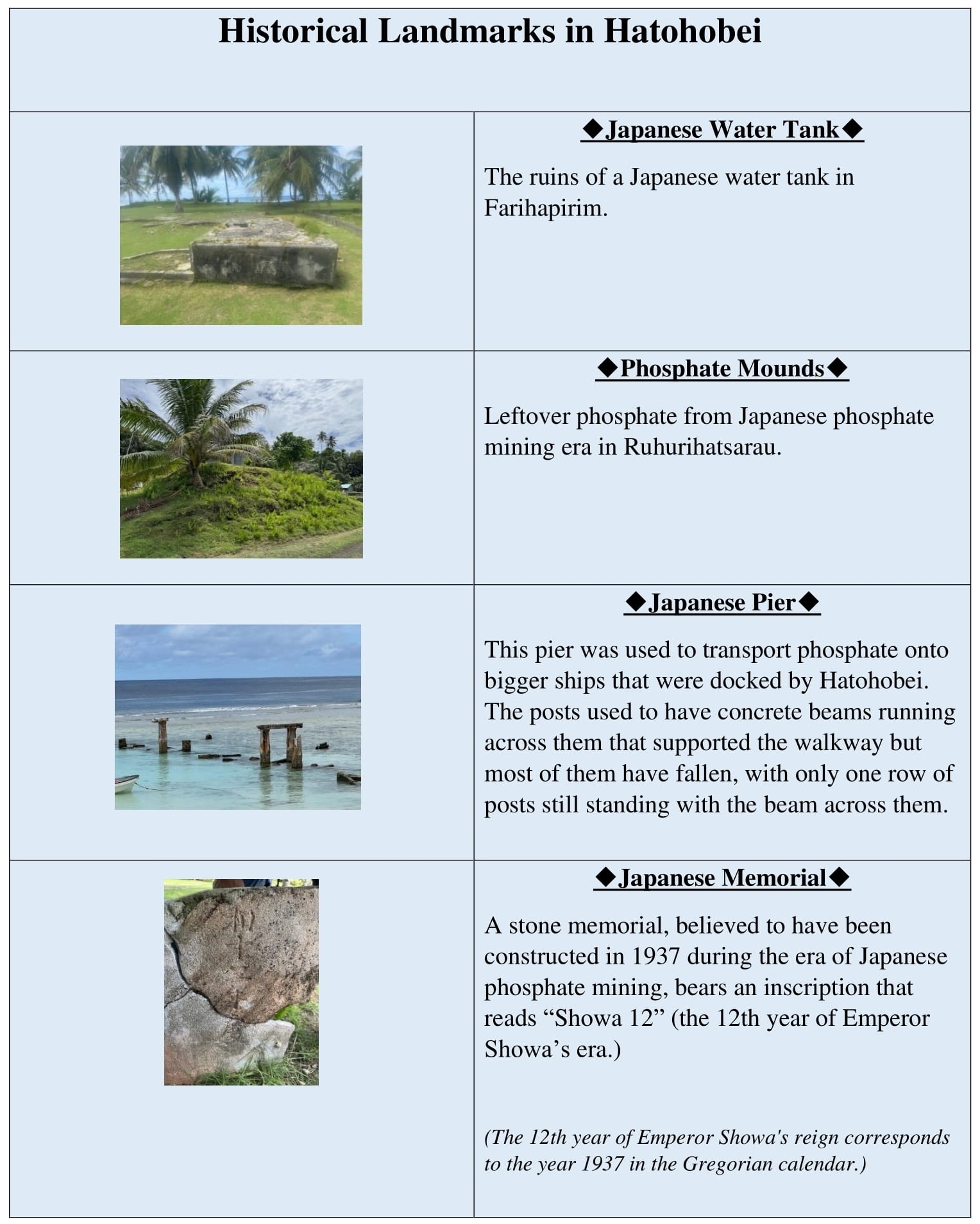

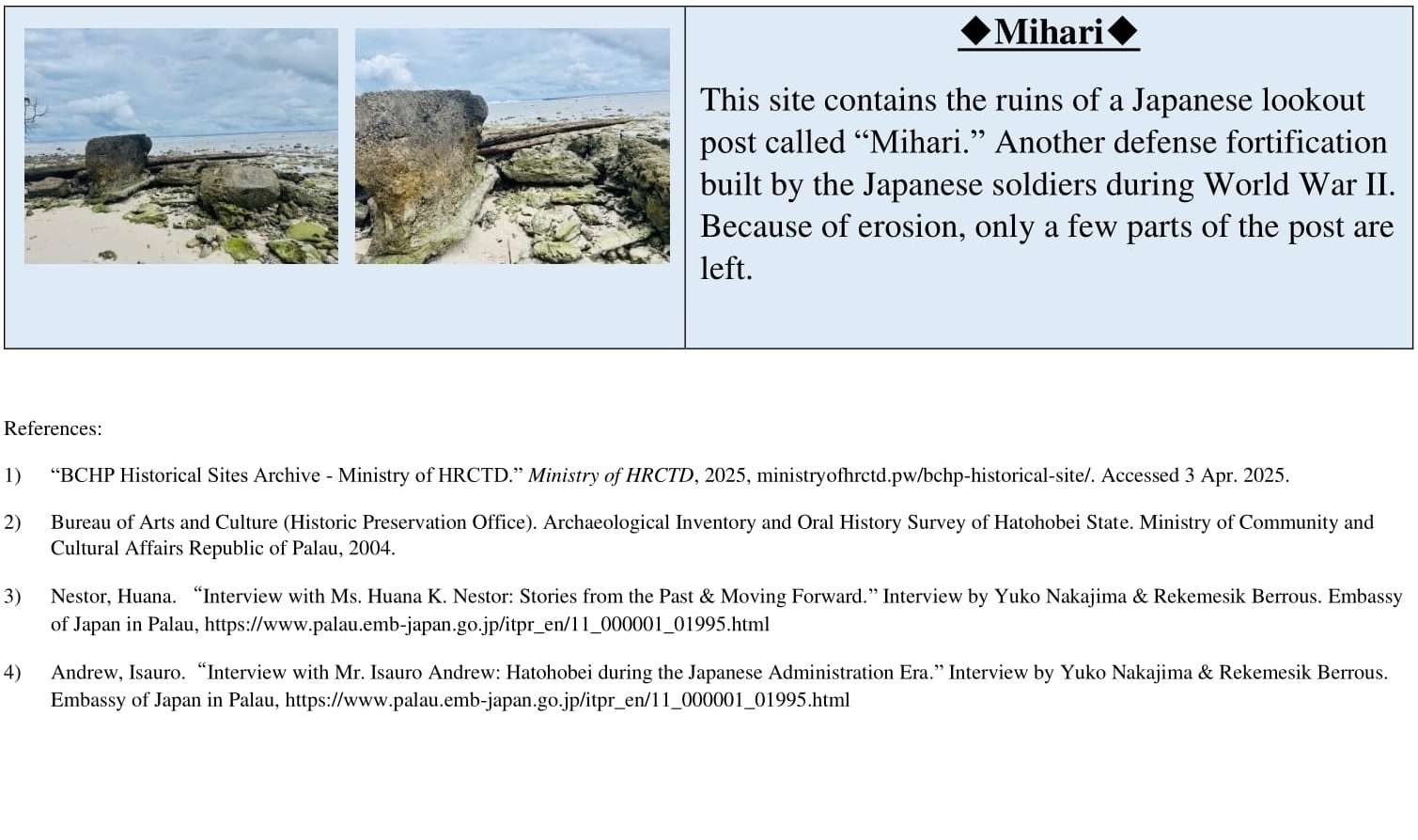

While her focus remains on cultural preservation, Ms. Huana was able to provided information about key historical landmarks on Hatohobei, many of which date back to the Japanese occupation. These sites include phosphate mounds, an old Japanese water well, and a railway system that was used to transport phosphate from the mines to the pier. Other important landmarks include Miharidai (lookout points), a stone path with cross markers, and an old church that contains the graves of Japanese soldiers.

Ms. Huana shared stories her mother told her about the war. Villagers would cook and deliver food to the Japanese troops stationed at Hatohobei, and the older generation referred to this food as “kan.” During the war, enemy aircrafts often targeted the Japanese soldiers' food supplies. Driven by extreme hunger, some soldiers tried to steal extra rations from local villagers, but their actions were met with punishment from their commanding officers.

After the war, her family received postwar repatriations in the form of money. Ms. Huana recalls that the first check that they received was when she was in the 6th grade and lasted until she was in the 9th grade. Her mother explained that it was compensation for the war’s damage to Hatohobei and its people.

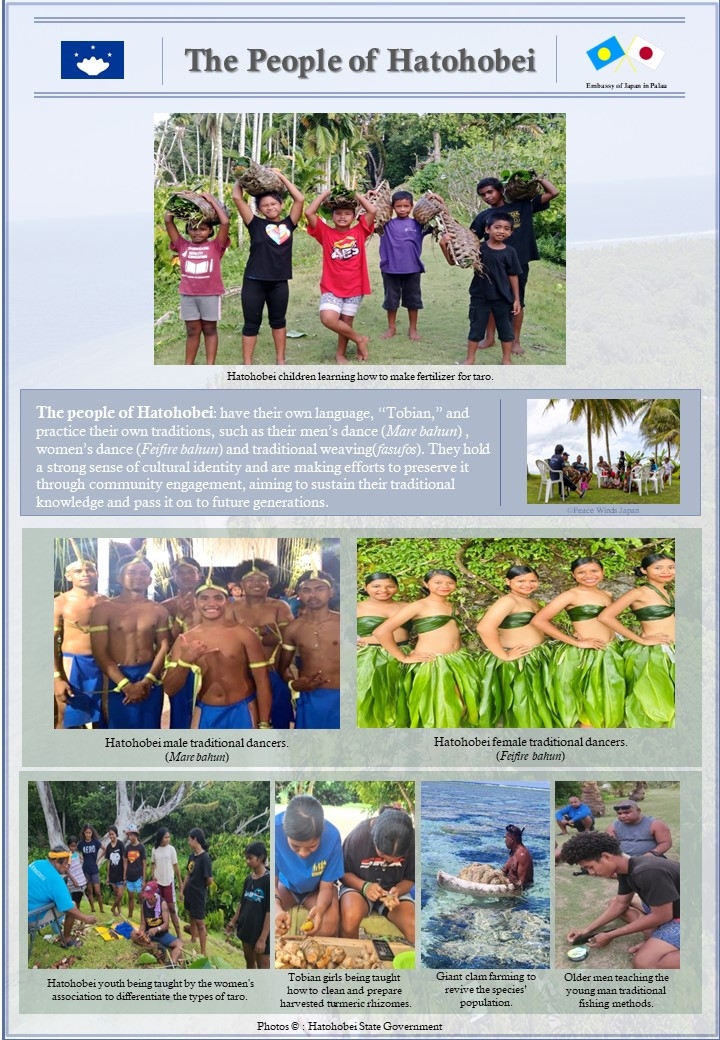

Ms. Huana informed us that she and the Hatohobei Women’s Association have been able to hold workshops, funded through various grants, to teach young people traditional practices such as fishing, weaving, taro harvesting, and cooking.

She emphasized the importance of preserving the traditional practice of taro planting and harvesting, as it holds a significant place in the history of Hatohobei State. Ms. Huana tells us that there were once no taro patches in Hatohobei. In response to food scarcity, the villagers decided to create land suitable for taro cultivation. Every day, they would dig into the ground using coconut husks to form deep craters, then fill them with sticks, dead leaves, grass clippings, and food waste to create nutrient-rich soil for taro planting. Today, the center of Hatohobei is home to numerous taro patches, a reminder of the hard work and determination of past Tobian villagers, who labored so that their families and future generations could live off the land.

The Women’s Association has also been working to revive the Hoho Festival, a traditional celebration that has not been held since the 1960’s. Reviving the festival is seen as an important step in reconnecting the community to its cultural roots and ensuring that these traditions are maintained for years to come.

Despite the historical challenges, Ms. Huana and the Women’s Association remain committed to preserving and promoting Tobian culture. Their ongoing efforts are crucial in ensuring that future generations understand their heritage and continue to uphold it.

While her focus remains on cultural preservation, Ms. Huana was able to provided information about key historical landmarks on Hatohobei, many of which date back to the Japanese occupation. These sites include phosphate mounds, an old Japanese water well, and a railway system that was used to transport phosphate from the mines to the pier. Other important landmarks include Miharidai (lookout points), a stone path with cross markers, and an old church that contains the graves of Japanese soldiers.

Ms. Huana shared stories her mother told her about the war. Villagers would cook and deliver food to the Japanese troops stationed at Hatohobei, and the older generation referred to this food as “kan.” During the war, enemy aircrafts often targeted the Japanese soldiers' food supplies. Driven by extreme hunger, some soldiers tried to steal extra rations from local villagers, but their actions were met with punishment from their commanding officers.

After the war, her family received postwar repatriations in the form of money. Ms. Huana recalls that the first check that they received was when she was in the 6th grade and lasted until she was in the 9th grade. Her mother explained that it was compensation for the war’s damage to Hatohobei and its people.

Ms. Huana informed us that she and the Hatohobei Women’s Association have been able to hold workshops, funded through various grants, to teach young people traditional practices such as fishing, weaving, taro harvesting, and cooking.

She emphasized the importance of preserving the traditional practice of taro planting and harvesting, as it holds a significant place in the history of Hatohobei State. Ms. Huana tells us that there were once no taro patches in Hatohobei. In response to food scarcity, the villagers decided to create land suitable for taro cultivation. Every day, they would dig into the ground using coconut husks to form deep craters, then fill them with sticks, dead leaves, grass clippings, and food waste to create nutrient-rich soil for taro planting. Today, the center of Hatohobei is home to numerous taro patches, a reminder of the hard work and determination of past Tobian villagers, who labored so that their families and future generations could live off the land.

The Women’s Association has also been working to revive the Hoho Festival, a traditional celebration that has not been held since the 1960’s. Reviving the festival is seen as an important step in reconnecting the community to its cultural roots and ensuring that these traditions are maintained for years to come.

Despite the historical challenges, Ms. Huana and the Women’s Association remain committed to preserving and promoting Tobian culture. Their ongoing efforts are crucial in ensuring that future generations understand their heritage and continue to uphold it.

Interview with Mr. Isauro Andrew: Hatohobei During the Japanese Administration

On February 10, 2025, The Embassy interviewed Mr. Isauro Andrew a Hatohobei elder who was born in 1943, two years before the end of World War II. Mr. Isauro was able to shed light on the history of Hatohobei before and during the war.

Mr. Isauro explained to us that because of how young he was, he didn’t have the clearest memory of the happenings before, during, and right after the war. Even though he was too young to remember, he was able to hear first hand accounts from older family members and villagers.

He was told that at the height of the phosphate mining times, there were many Japanese workers who were stationed in Hatohobei, to mine for phosphate from the Nanyo Boeki Kaisha, or “Nambo” as remembered by Mr. Isauro. The villagers of Hatohobei also helped the workers, collect and transport phosphate. Workers even had to construct an access channel deep enough for larger ships to approach the island more easily to collect phosphate. This channel also inadvertently helped local fishermen. It allowed them to venture out without worrying about the tides, making fishing more accessible for the locals. Mr. Isauro explained that there used to be mounds of phosphate littered all over the island. The digging was so extensive that it led to the formation of craters, which eventually turned into natural pools. However, due to the degraded soil structure, the villagers were no longer able to use the land for farming.

The phosphate mining wasn’t the only business on Hatohobei and its surrounding islands. Mr. Isauro informed us that there were companies for sea cucumber processing, katsuo-bushi “bonito flakes”, and even a turtle shell collecting and processing business.

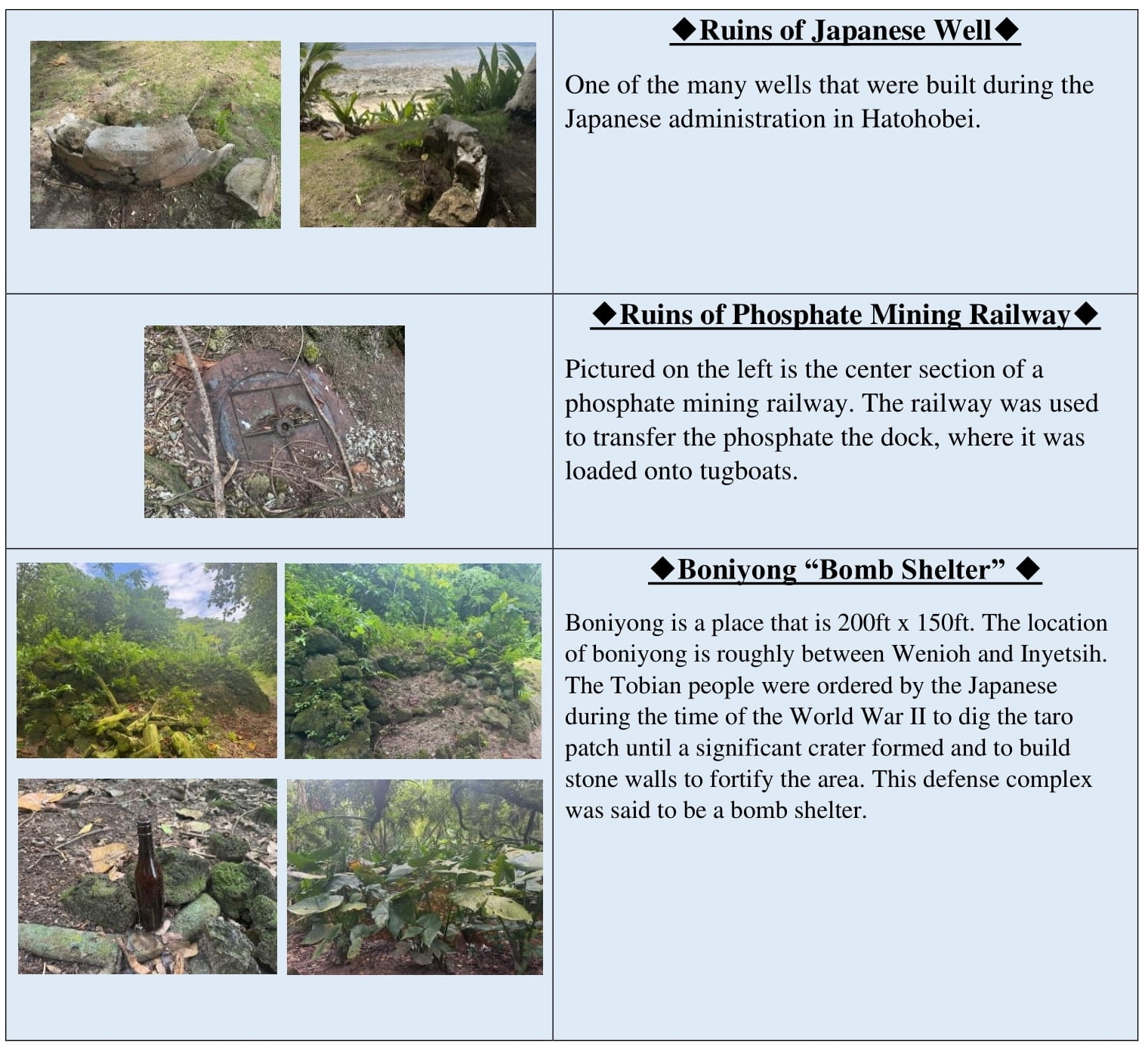

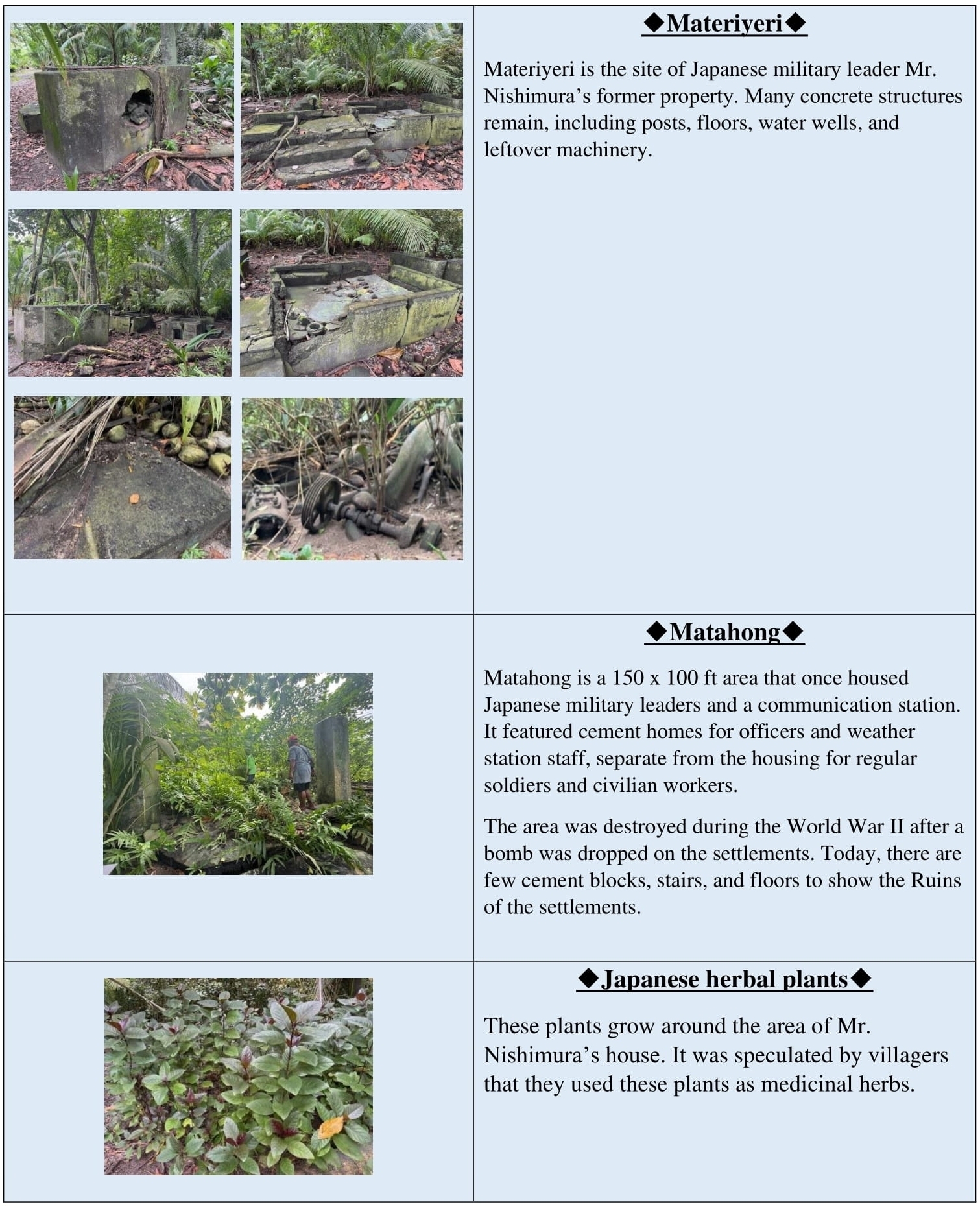

Once the Japanese troops arrived to Hatohobei, many, if not all the Japanese workers that were stationed by “Nambo,” left the island. During the war, locals were asked by Japanese soldiers to watch for enemy ships and aircraft. The Japanese also constructed many bokungo (air raid shelters), but because these were made of wood and other simple materials, most have deteriorated over time. Few, if any, remain today as told by Mr. Isauro.

We were also told that the remaining villagers who did not go to Fanna, an island territory of Sonsorol state, lived on the north side of the island while the soldiers occupied the southern half.

We asked Mr. Isauro if there were any civilian casualties and he said that there hadn’t been any, most of the bombing was focused on the Japanese soldiers compounds or in the sea. Mr. Isauro also explained that some soldiers had to resort to stealing from villagers taro patches or and farming areas so they could stave off starvation. This was quickly met with harsh punishment from their commanding officers.

The information provided by Mr. Isauro offers a deeper understanding into life on the island and the experiences of the Tobian people during a tumultuous time, highlighting how war affects not only the nations directly involved, but also the countless soldiers and smaller, often overlooked nations caught in its wake.

Mr. Isauro explained to us that because of how young he was, he didn’t have the clearest memory of the happenings before, during, and right after the war. Even though he was too young to remember, he was able to hear first hand accounts from older family members and villagers.

He was told that at the height of the phosphate mining times, there were many Japanese workers who were stationed in Hatohobei, to mine for phosphate from the Nanyo Boeki Kaisha, or “Nambo” as remembered by Mr. Isauro. The villagers of Hatohobei also helped the workers, collect and transport phosphate. Workers even had to construct an access channel deep enough for larger ships to approach the island more easily to collect phosphate. This channel also inadvertently helped local fishermen. It allowed them to venture out without worrying about the tides, making fishing more accessible for the locals. Mr. Isauro explained that there used to be mounds of phosphate littered all over the island. The digging was so extensive that it led to the formation of craters, which eventually turned into natural pools. However, due to the degraded soil structure, the villagers were no longer able to use the land for farming.

The phosphate mining wasn’t the only business on Hatohobei and its surrounding islands. Mr. Isauro informed us that there were companies for sea cucumber processing, katsuo-bushi “bonito flakes”, and even a turtle shell collecting and processing business.

Once the Japanese troops arrived to Hatohobei, many, if not all the Japanese workers that were stationed by “Nambo,” left the island. During the war, locals were asked by Japanese soldiers to watch for enemy ships and aircraft. The Japanese also constructed many bokungo (air raid shelters), but because these were made of wood and other simple materials, most have deteriorated over time. Few, if any, remain today as told by Mr. Isauro.

We were also told that the remaining villagers who did not go to Fanna, an island territory of Sonsorol state, lived on the north side of the island while the soldiers occupied the southern half.

We asked Mr. Isauro if there were any civilian casualties and he said that there hadn’t been any, most of the bombing was focused on the Japanese soldiers compounds or in the sea. Mr. Isauro also explained that some soldiers had to resort to stealing from villagers taro patches or and farming areas so they could stave off starvation. This was quickly met with harsh punishment from their commanding officers.

The information provided by Mr. Isauro offers a deeper understanding into life on the island and the experiences of the Tobian people during a tumultuous time, highlighting how war affects not only the nations directly involved, but also the countless soldiers and smaller, often overlooked nations caught in its wake.